If you’re like us, and whole religions are being launched to prevent that, you have your own personal stories of problems in global supply chains the last two and a half years. Maybe you couldn’t find your favorite yogurt or like us you had to wait eight months for the faucet you’d ordered for your bathroom remodel. There are so many stories like these that a narrative developed (always beware the tyranny of narratives) that global supply chains are fragile.

Over the last two years we’ve seen a multitude of headlines along the lines of: “supply chain fragility and globalization’s future”, or “How the Ever Given exposed the fragility of global supply chains.” But when people say global supply chains are fragile, they are leaving out a key phrase: “compared to what?” What if each country produced everything in house? And then they had to shut down, including farms and factories and deliveries because of one calamity or another such as a pandemic? Suddenly these countries would be negotiating with other countries for essential goods but it would take a long time to receive them since there would be no global supply chain system in place. And we would all have more expensive products and less choice without global supply chains. These headlines, the concerns about global supply chain fragility, are part of an ongoing backlash against globalization. The world that so many seem to be pining for where globalization goes away, ironically in part to fix the supposed fragility of global supply chains, would in fact be far more fragile.

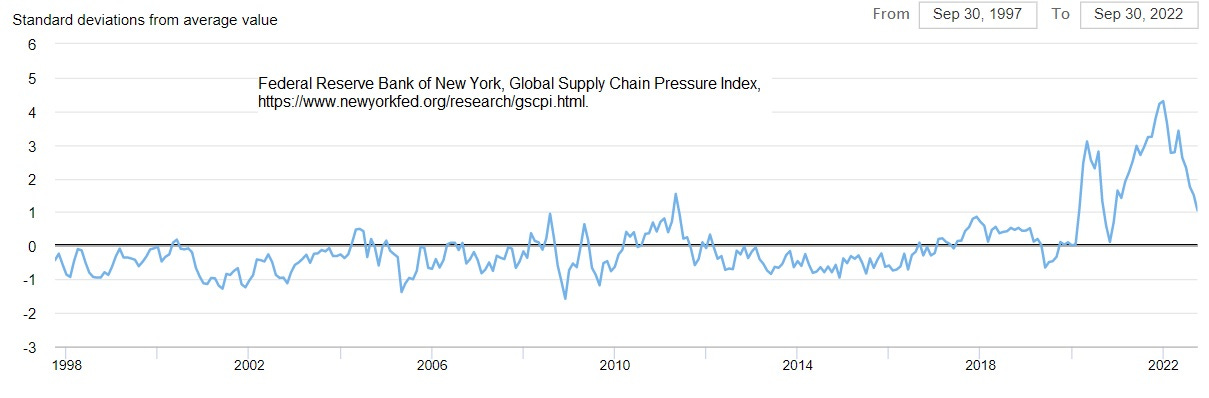

There were stresses in global supply chains the past two years no doubt as Americans and others transformed from spending on vacations and eating out to buying a wide variety of goods. This increase in buying things instead of services taxed the global supply chain system. As more goods came from Asia, especially China, the global supply chain infrastructure could not fully handle the surge.

But despite problems, global supply chains held up better than anyone might have expected. Despite the worst pandemic since 1918 and the worst war in Europe since World War II, there were no famines the last two years, no one died from lack of medicine or other essential materials. Yes, we had to wait months for the model of SUV we wanted or couldn’t find the flavor of ice cream we are used to, which is not optimal, but not a disaster. When considering all the circumstances global supply chains grappled with, they held up pretty well.

Global Supply Chains Saved the World

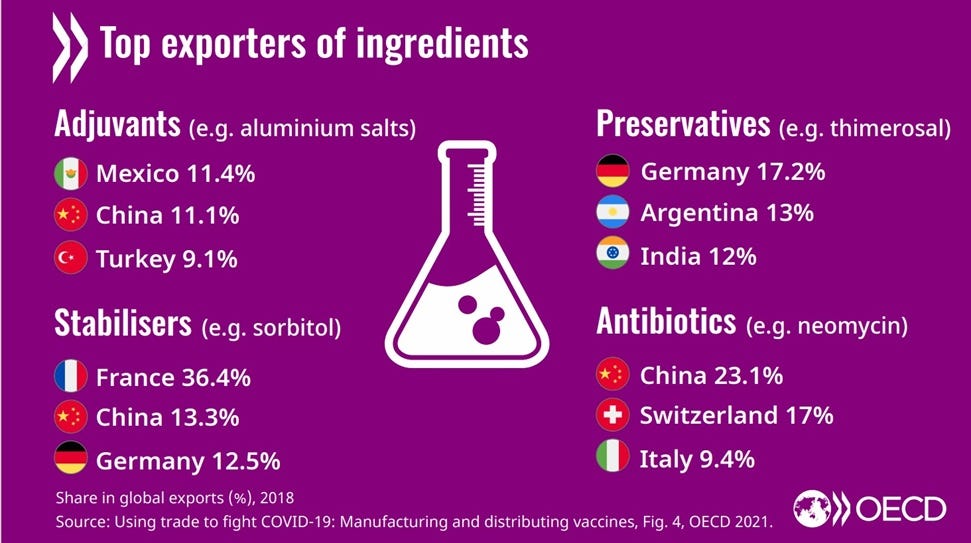

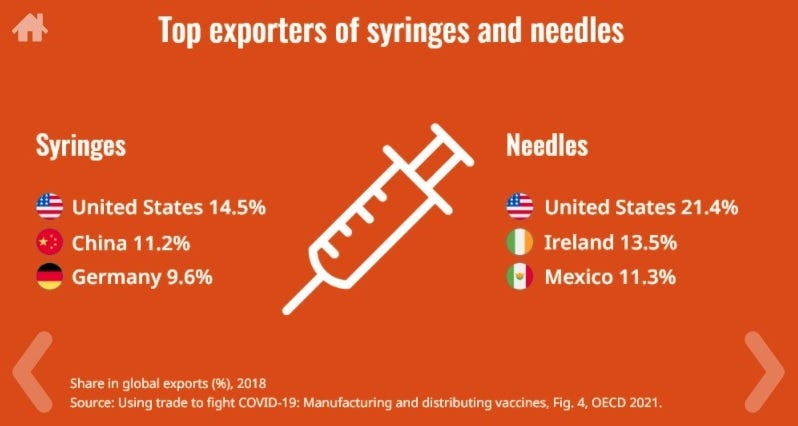

In fact, not only did global supply chains prove to be less fragile than feared, they actually helped save us the last two plus years. Vaccines, the factor that is helping us to exit the pandemic, are a wonder of globalization and global supply chains. Last year, the OECD—the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—released a paper on the various aspects of Covid-19 vaccines. As you can see in these two OECD graphics, the ingredients and components needed for the vaccines are sourced from many places. China plays a large role, but so too do India, Argentina, Germany and Mexico. Nearly every continent is represented.

And vaccines that require refrigeration? A variety of countries export the various components necessary for keeping the vaccines safe and sound, including, yep, Romania and Mexico. And what about the development of the vaccines? They were a product of scientific cooperation across many countries, as you see in this OECD graphic. Open information and scientific collaboration—globalization--is how we are getting out of the pandemic.

Let’s dig a little deeper into global supply chains for vaccines. The ability to quickly increase production, supply and trade in global vaccines trade was astonishing. And yet we seem to just take it for granted. According to the OECD, “the value of global trade in vaccines, that is all types of vaccines for human medicine in the first six months of 2021 was 26% higher than for the whole 12 months of 2020, and 30% higher than in 2019.”

Or, what about other medical supplies, including masks? You may remember in the first weeks of the pandemic there was a shortage of masks. In fact, in a remarkably short-sighted move, the U.S. CDC disparaged the utility of masks and encouraged people not to use them in an effort to ensure enough masks for health care workers. There was a mask shortage at the very beginning of the pandemic but it didn’t last very long. Again, the OECD study tells us: “imports of face masks rose from a monthly value of around USD 240 million in March 2020 to USD 3.7 billion in May 2020 – a more than 15-fold (+1 449%) increase in just three months The number of units imported experienced a similar increase (+1 447%) – from 600 million items to 9.4 billion items over the same period – so the surge isn’t driven by higher prices.”

The mask shortage was solved in a month. Again, this is due to global supply chains incredible success. And yet, we mostly took it for granted or complained about how long it was taking to get a desk we ordered through Wayfair. We ignored the miracle happening before our eyes.

One of the reasons for the short-term shortage was China made most of the masks. But in solving the shortage, data shows there was a diversification of suppliers. Again the OECD report tells us, “While China accounted for about 94% of the value of disposable face masks imported by the United States in July 2020, the origin of disposable face masks has since diversified with new suppliers emerging: Mexico, Korea, and other countries accounted for 11%, 5% and 4% respectively of the United States’ imports of face masks in November 2021.”

But China is still by far the largest producer. And this leads us to how we can build more resilience in global supply chains and make them less fragile. We need a lot more diversification of global supply chains.

Diversify Out of China

Global supply chains did show some stress over the last two plus years. Part of this was because of an over emphasis on “just in time” models. But part of this is because too many products still have final assembly or rely on too many components from one country: China. There are geostrategic reasons to reduce reliance on China for the supply chain, but there are also resilience reasons.

There was a slow diversification occurring out of China pre-dating the U.S.-China trade war and the Covid pandemic. United States electronic imports from China dropped 10 percent from 2018 to 2021. The U.S. didn’t start re-shoring this production, it started importing more from Southeast Asia.

There has been some diversification from China, but it’s still relatively modest. But the shift has started to happen. Much of it went to Vietnam. I visited a shoe factory in Vietnam last month. It moved from China to Vietnam in 2014. That’s long before the pandemic and even before the U.S.-China trade war. Certain lower-value manufacturing and assembly was already beginning to move out of China for cost reasons. China had become too expensive for certain activities.

However, the movement to Southeast Asia until recently was mostly in lower value goods. Countries such as Vietnam and others began to take over final assembly. But final assembly is lower down in the value chain. China’s overall manufacturing levels remained consistently high even during the global recession that occurred during the early part of the pandemic. Too many products, too many components of products are still manufactured in China. But, that is continuing to change, even in the last four or five months.

Apple is Diversifying Out of China

Let’s look at Apple as an example of some changes that have happened and what may occur going forward. This is drawing from analysis at macropolo.org. Apple has moved some manufacturing and assembly sites out of China. According to macropolo’s analysis, “Many of the sites Apple removed from China were specializing in labor-intensive work such as packaging and metal production. At the same time, Apple added 14 new Chinese suppliers to its roster in 2021, many of which were higher value, knowledge-intensive manufacturers of intermediate goods like optical components, sensors, and connectors.”

Again, much of this work was moved to Southeast Asia with Vietnam being the main beneficiary. It was easy for Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese companies that are suppliers of Apple to do so because they already had facilities in Vietnam. This allowed them to utilize their contacts, expertise and experience there to do work for Apple in Vietnam.

Apple made a good start diversifying out of China in 2021, although as macropolo.org states, it was still a modest amount. But diversification has sped up even in the last half year. The Wall Street Journal reported that Apple is talking of moving even more plants out of China due to the severe lockdowns China has imposed the last few months. And some of these components and products are further up the value chain, such as airpods. Vietnam is not just making shoes anymore. And India is increasingly becoming an option for high tech manufacturing, not China. The trade war and pandemic got things in motion but China’s own policies are likely to really move the world towards diversifying global supply chains.

People don’t realize what an impact China’s Zero Covid policy and its shutdown of Shanghai and other cities has had on companies. It’s one thing if China is committing genocide against Uyghurs, arresting hundreds of human rights activists and cracking down on feminists. But when doing business there becomes completely unreliable? That’s a bridge too far…at least for companies.

Money, as always, is the incentive for change, and it is impelling companies to more deeply diversify out of China. This will make global supply chains, which were more resilient than we give them credit for during the pandemic, even more so. I had to wait eight months for the specific polished-nickel with the right shaped spout bathroom faucet because of supply chains. There’s a good chance in the next worldwide emergency, if we continue to diversify global supply chains, my non-China manufactured faucet will arrive much faster. But let’s hope I’m not doing more remodels anytime soon, other than of supply chains.