China Policy in the Next Administration Part I

What will China policy be in a Trump or Harris Administration? First, let's understand what are the circumstances in which a new administration will operate

As fate would have it, the United States is going to have a new president come November. That means China policy will change. The next president will either be Donald Trump or Kamala Harris. Given the importance of the issue to the country and world, it’s worth thinking through what are the likely China policies of these two.

But before we dive into the two candidates possible China policies, it’s important to understand various aspects of the U.S.-China relationship that are universal, that will be true no mater who becomes president, even if you or I become president, as unlikely as that might be even in this strange, plot-twisting election season.

Tensions Aren’t Going Away

For some foreign policy experts, reducing tensions is the end all and be all of U.S. China policy. But that’s mistaking a condition for a symptom. The tension springs from the fact that China has become more authoritarian and more expansionist over the last decade and the United States and many other countries want to counter that. Unless China stops being authoritarian and/or expansionist, or unless many countries decide they are fine with China being authoritarian and expansionist, there will be tensions in not just the U.S. - China relationship but in many countries relationships with China.

We outlined China’s authoritarianism and expansionism extensively in our book, Challenging China, in numerous posts in our weekly International Need to Know newsletter and in previous Substack articles so won’t belabor it here other than to say China continues to oppress its people, including denying basic freedoms of expression, everything from feminist views to religious beliefs. And it has become even more expansionist over the last few years including in shoals off the coast of the Philippines in the South China Sea, setting up military bases in Cambodia, supporting dictators in Venezuela or supporting the death cult that is Russia. Plus, China continues to change the previous rules-based international order into one that makes the world safe for authoritarianism. That’s why there is tension in the U.S.-China relationship, and indeed in the India-China, Japan-China, E.U.-China and many other relationships.

China’s Economy Will Continue to Grow Slowly

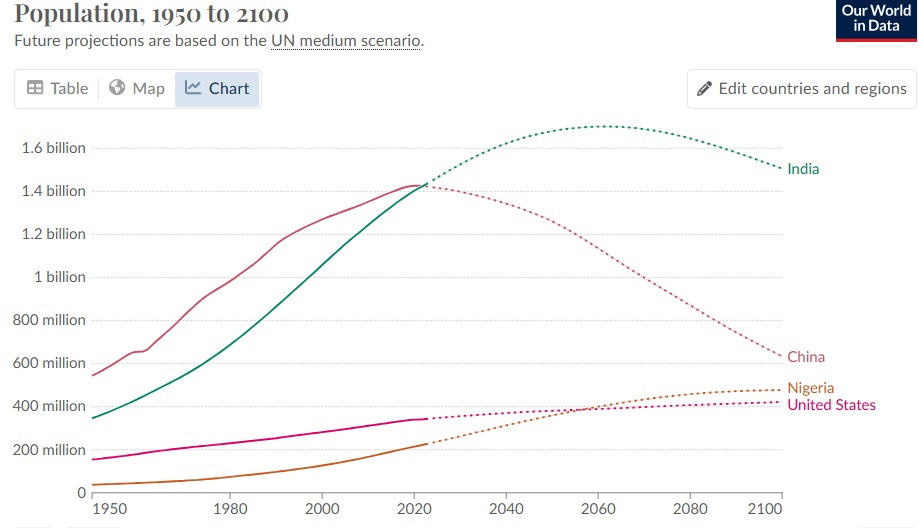

As we correctly predicted in our book, China is now in a slow growth economy. The previous Goodfellas era economy ended due to a purposefully popped real estate bubble, high debt (mainly at the local and provincial level), less productive investment, and aging demographics. China’s leadership is showing no signs of trying to re-inflate the real estate bubble, nor should they. At the same time, they are having troubles instituting policies that favor households over industry. And each coming year China’s population is likely to decrease until, if current trends continue, it shrinks to less than half its current population by the end of the century. Even the 5 percent GDP growth that China currently claims is likely aspirational data. China more than likely grew far less than five percent last year and probably is growing less than it claims this year.

China’s Economic Approach Creates Confrontation

China’s economic approach, reconfirmed by the recent Third Plenum, is to build up its strategic industries, be self reliant and continue to rely on exports, Yes, there is again talk of “common prosperity,” the concept that government will institute policies to spread wealth more widely and help households rather than just industry. So far, however, there has been lots of common prosperity talk but very little action. After the Third Plenum it appears there might be some movement on Hukou reform, a system of household registration which has limited educational and economic opportunities for rural residents. If China actually implements Hukou reform it will be helpful to restructuring its economy and reducing inequality (China, believe it or not, is about as unequal as the United States).

But most of China’s economic efforts continue to be focused on building up what it considers strategic industries, whether cars (increasingly EVs), machinery, AI, semiconductors and others such sectors. This is both to help these industries but also to make China less reliant on other countries for various strategic goods. This is reflected in the trade data. China’s exports continue to go up while its imports stagnate as Brad Setser’s graph below shows (Setser has been doing remarkable work understanding China trade beyond China’s official data).

And it’s not just overall imports but intermediate imports as well. Increasingly Chinese companies are making most of the components of the products. This leads to:

Countries, not just the U.S., pushing back on China’s Exports Policy

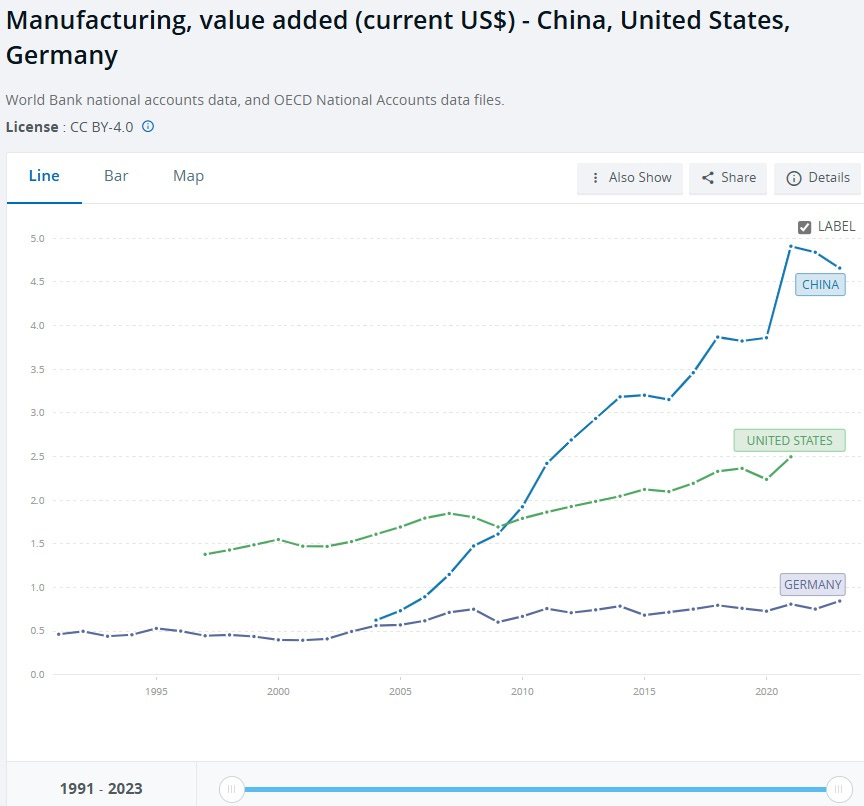

China wants to build up its industries and export the resulting products. This leads to China’s GDP accounting for 17 percent of world GDP but its manufacturing capturing 31 percent of global manufacturing. Great, right? Well, the problem is other countries are increasingly tired of ceding industries to China and importing China’s excess capacity. Yes, the United States has instituted tariffs on China but so too have the E.U., Mexico, Brazil and a swathe of other countries. In fact, Mexico’s Finance Minister recently complained “China sells to us but doesn’t buy from us and that’s not reciprocal trade.”

This tension between China’s desire to export its way out of its economic challenges, build up its strategic industries and become mostly self-resilient across most sectors against the fact other countries also want to be competitive and are increasingly tired of importing from China will be resolved one way or another. The resolution will impart consequences for economies all over the world and for the geopolitical landscape.

China will continue to be expansionist

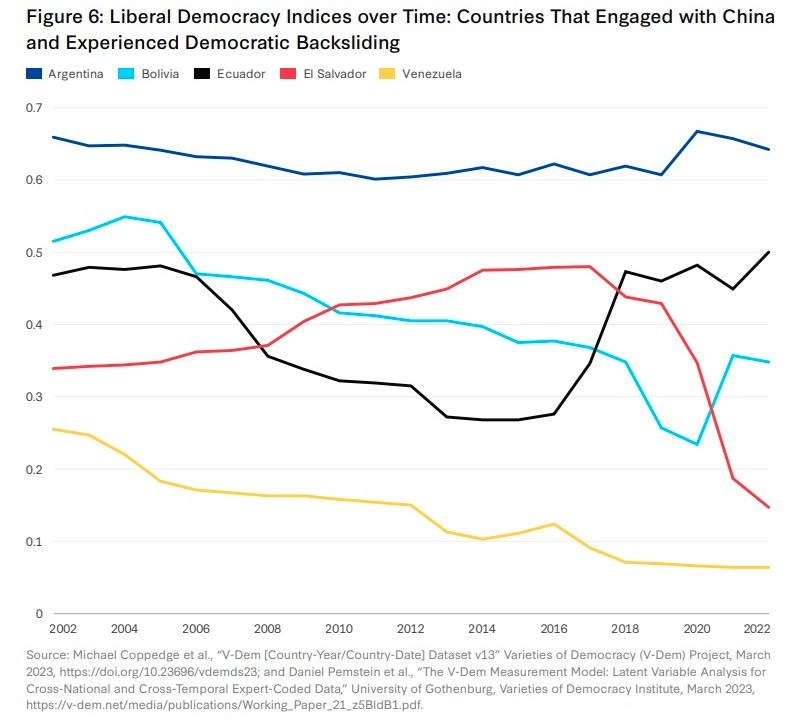

China is increasingly aggressive in the world and that will not change during a new U.S. administration. Certainly in the South China Sea, China has asserted itself in the 2nd Thomas Shoal with the Philippines and most recently in the Sabina Shoal, only 75 miles off the Philippines Coast and more than 500 from China’s. It sends ships into Malaysia’s exclusive economic zones and it intimidates Vietnam with new capabilities through infrastructure in Cambodia. And, of course, it continually threatens Taiwan in both word and deed. But China’s ambitions are not just in Asia. The Center for Strategic and International Studies recent report, Exporting Autocracy, details the way China encourages democratic backsliding in Latin America. China wants to exert its will around the world and to make the world safe for authoritarianism.

This is the landscape in which a new U.S. administration will operate. Given all of the above, what will a Trump or Harris administration China policy be? We’ll delve into those specifics later this week, starting with Trump and then Harris.